Our legal expert continues Bill Augello’s educational tradition by magnifying some of the fundamentals that shippers need to understand in order to minimize costs and alleviate risks in their logistics organizations.

By Brent WM. Primus, J.D., Primus Law Office, P.A. -- Logistics Management, 2/1/2008

I would first like to thank the staff of Logistics Management for allowing me the opportunity to continue the work that my colleague and mentor Bill Augello began 50 years ago to make shippers better aware of the legal aspects of logistics. Bill strongly believed, as do I, that shippers must educate themselves on the relevant laws of transport in order to minimize the costs and risks that are inherent when dealing with carriers.

However, there is at least one other reason why shippers should educate themselves on all aspects of transportation law: career growth. Bill was once quoted as saying “one of my goals is to help each transportation professional move one rung up on the corporate ladder.” For transportation managers, it’s the knowledge of the laws affecting logistics that will empower them to take that next step. Now, let’s continue the journey Bill started.

5 challenges for shippers

1. Determining and documenting a carrier’s rates and charges. Just as the operational essential of logistics is getting an item from Point A to Point B, the economic essential of the transaction is the establishment and payment of a carrier’s rates and charges. A freight bill is not created out of thin air, and a shipper must fully understand the basis for the carrier’s calculations of its freight charges.

Here are some of the questions that need to be asked to meet this challenge:

* Are the rates based on a carrier’s published tariffs and rate schedules or on an individual negotiation?

* If they are based on a “published” schedule, where is it found?

* What are all the details, variations, and permutations of the schedule?

* Are there things that a shipper can do—for example, altering the size, shape, or weight of the basic “shipping unit”—that would result in lesser charges?

* If rates are based on an individual negotiation, how has the negotiation been documented? In a handshake? (I hope not.) A multi-page contract? (This is the best solution when done correctly.) A one page “pricing agreement?” (Such agreements are good for documenting rates but leave in place the carrier’s tariff terms and conditions.)

* However documented, are there other documents or publications “incorporated by reference” that could affect the pricing? An example of such a publication would be a carrier’s rules tariff or the National Motor Freight Classification. If so, a shipper needs to know exactly what is being incorporated and how it will affect the final charges of the carrier.

2. Determining the limits of liability. Unrecovered claims for loss and damage to cargo in transit are just as much a cost to a shipper as is payment of a carrier’s freight bills. As a general proposition, during the period of regulation of the railroads and motor carriers, the “default provision” for recovery of loss and damage claims was the “actual loss or injury”—that is, a full monetary recovery by the shipper.

This meant that there was no affirmative action required of a shipper at the time that the goods were tendered to the carrier in order to later make a full recovery in the event of a loss. The opposite is true today. Railroads and trucking companies are now allowed by statute to establish less than full value limits of liability. All of the larger ones have done so. For example, most motor carriers have established a limit of $25 per pound; however, many have also put into place a limit of $1 per pound for so-called “expedited shipments.”

Thus, in the absence of an individually negotiated contract, a shipper now has to take an affirmative action; that is, declare a value at the time of tender to the carrier, as well as pay a higher charge, in order to obtain a full or higher recovery in the event of loss. Shippers must realize that limits of liability vary from mode to mode, and, within a mode, individual companies can establish their own limits of liability. Further, a particular carrier may establish different limits of liability for different products.

If a particular carrier’s standard limit of liability is insufficient to cover the product shipped, then a shipper must consider possible solutions. This could include declaring a higher value for all or some shipments, negotiating a higher limit of liability, or obtaining some form of shippers’ interest cargo insurance policy.

3. Determining the time limits for filing claims for overcharges and for loss and damage. Just as the carriers of various modes have established different and varying levels of liability, they have also established varying time limits for filing claims. Generally speaking, the time limit for filing a loss and damage claim against a motor carrier is nine months from the date of delivery. For air carriers it can be much shorter—30 days or less.

Similarly, time limits for filing claims and lawsuits for refunds for overpayments of freight charges are also subject to time limits. Again, these vary from mode to mode and from carrier to carrier. It’s up to the shipper to learn what they are as the carriers are not known for initiating such conversations.

4. Becoming an advocate for shipper interests and issues. With the demise of the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) and similar government agencies, who now watches out for the economic interests of shippers? The short answer is no one but the shippers themselves.

You can be assured that the carriers are well organized and have effective advocates and lobbyists in matters that affect them financially. Carriers have a definite advantage in that transportation is the core business of their company while for shippers, such as manufacturers, transportation is often viewed as a necessary evil rather than as a critical part of the supply chain.

Thus, a transportation manager has to not only advocate a shipper’s position with respect to the outside world, but also with respect to the management of their company. This means that transportation managers have to continually ensure that senior-level management understands the significance of what the transportation managers are doing.

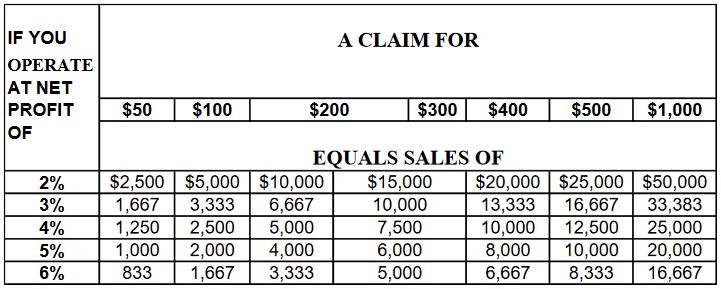

A good example is in the area of claims management and recovery. Figure 1, prepared by Bill Augello, illustrates the importance of recovering claims for loss and damage and shows how unrecovered claims can erode a company’s profitability.

Shippers also need to educate top management as to the economic affect that proposed legislation may have on the company. Shippers may lobby for or against legislation by working individually with their state or federal legislators or collectively through trade organizations. When shippers are acting through an organization, the organization is only as strong as the support the members give the organization.

5. Staying current. After you’ve learned the fundamentals of logistics and the law it’s imperative that you stay current on developments in the industry as well as changes in the related laws. Following are some examples from the last year or so.

* Motor. Many readers may have heard of the case of Schramm v. Foster which is colloquially known as the “CH Robinson case.” In that case, the trial Judge refused to grant Robinson’s request to dismiss the case because the Judge believed that, on the preliminary facts before him, a reasonable jury could conclude that Robinson (acting as a broker) had been negligent in selecting the carrier that was involved in a very serious accident. Subsequently, a New Jersey Court found in Puckrein v. BFI, Inc., et al. that the shipper was liable for selecting an unsafe carrier.

This is an issue that will be with us indefinitely and affects shippers, intermediaries, and even carriers who “hire” motor carriers—especially truckload carriers. As recently as September 2007, a U.S. District Court in the case of Jones v. D’Souza ruled against CH Robinson in a situation very similar to that of the Schramm case. Any transportation professional involved in selecting and monitoring carriers must know and implement measures to minimize its company’s exposure to such claims.

Also in 2007, the Surface Transportation Board (STB) issued a bombshell ruling determining that the antitrust immunity for Tariff Bureaus was no longer appropriate. One consequence of this is that the National Classification Committee (NCC) entirely reorganized itself into the Commodity Classification Standards Board (CCSB) going forward. Shippers whose company’s freight charges are based upon the National Motor Freight Classification (NMFC) system need to closely monitor further developments arising from this fundamental change.

* Rail. For rail shippers, there were two developments at the STB that could, depending on the circumstances, result in lower rates. In a proceeding known as STB Ex Parte No. 669, the STB sought public comments on how to interpret the term “contract” as it appears in the federal statutes. Then, in December of 2007, in a proceeding by Dupont against CSX (Docket No. 42099), the STB held that a “private quote” was not a contract.

The other development was in a decision entitled “Simplified Standards for Rail Rate Cases.” In this case, the STB announced a new, less expensive procedure for small shippers to challenge the reasonableness of a carrier’s rates that are subject to regulation.

* Ocean. Those involved in international trade—which these days is just about everyone—should know that a new international convention on the intermodal carriage of goods is in its final stages of negotiation within the United Nations Commission on International Trade (UNCITRAL).

It is expected that the convention will be approved by the United Nations General Assembly in the fall of 2008. If ratified by the United States in its present form, the convention will be a significant change from the Carriage of Goods by Sea Act (COGSA) that now governs loss and damage claims against ocean carriers.

On balance, the changes appear to be favorable for shippers. Accordingly, shippers affected by this change should closely monitor future developments. In particular, shippers should pay close attention to monitor any enabling legislation introduced into Congress to see what the final form will be and to decide whether or not to support its passage.

* Air. While there have been no major events over the last year, recent cases such as Treiber v. UPS demonstrate the need for shippers to understand what they are doing when they ship by air, when to rely on a carrier’s liability for claims, and when to purchase their own shipper’s interest policy of cargo insurance.

In the Treiber case, a jeweler shipped a piece of jewelry worth $107,000.00 but only declared a value of $50,000.00. The Court found that UPS was not liable as its tariff contained a provision stating that it would have no liability for packages tendered with a value in excess of $50,000.00. The Court went on to rule that the shipper was also not entitled to recover under the insurance policy it purchased through UPS since the policy terms mirrored the provisions of the UPS tariff.

Brent Wm. Primus, J.D., currently serves as the General Counsel for the Freight Transportation Consultants Association and is the CEO of transportlawtexts, inc. and Primus Law Office, P.A. Your questions are welcome at brent@primuslawoffice.com.Logistics Management Magazine is the co-sponsor of the On-line!, On-demand!! version of the seminar based on William Augello’s landmark text “Transportation, Logistics and the Law”